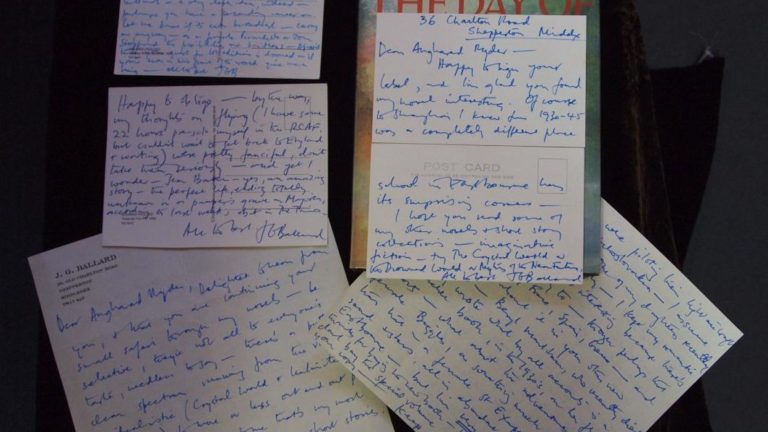

To illustrate how the discovery of a new place may influence the inner feelings of people, Enzo Fileno Carabba explained that it is wrong to identify Ballard as a creative artist because he is above all a person who is interested in the great changes of our society and who believes that they belong to specific alterations of the human mind.

The scholar advanced the idea that the presence of specific elements in the novels of Ballard, such as water, forests and deserts, are particularly useful for the writer because they help him to create a specific setting in which recreate the exchange between inner world and outer world. For him, Ballard plays with the power of imagination in order to shape the four elements of the planet Earth and create new worlds.[13] A great example is the adventure of Mallory in The Day of Creation. He has the power to give another life to the desert Sahara because he generates a river by removing the root of an old oak in the forest, but the reader remains uncertain till the end of the novel because he does not know if the river and the story of Mallory belong to reality. In other words, when Mallory said “I tried to stand back from my obsession with the river, but already I was thinking of the irrigation of the entire Sahara, of the transformation of the desert into the Edenic paradise that I saw around me in these green glades and sensed in its sweet airs. A new race would spring from Noon and myself as we lived peaceable in these forest bowers” [14], he is tried to imagine a life in a colonized country which is different from his mother country and, at the same time, to reflect on his life in an Edenic place which does not belong to the real world. With this in mind, it is possible to say that the colonized territory, with its heterotopic power, is able to create an Edenic reality in which Mallory can reflect on his own existence and imagine himself as a God who gives new life in an abandoned territory.

Various critics, in fact, agree that the exploration of landscapes conducted

by the characters created by Ballard are the result of the interaction between the inner world and the external world. For example, W. Warren Wagar conducted a study on the topographic analysis of Ballard’s novels, and he suggested that “Not only do the landscape mirror the soul; they help to shape and organize it. […] the action is, in fact, an interaction. The external world conditions us, but we in turn must engage and provoke the external world; there is, for Ballard, no way out of ourselves, no path to nirvana or transcendence or utopia, except by running the gauntlet of the world”15. In other words, Ballard is not interested in the personal story of the characters, but his main interest is to create mysterious landscape in order to have the perfect place to reach what Warren Wagar calls “the fulfilment of a spiritual quest”[16].

Not only The Day of Creation but also Heart of Darkness was analysed considering the secret of landscapes and geographical spaces. Mark D. Larabee asserted that, during the writing of the novella, Conrad made several alterations of the historical events of Congo especially in terms of geographical descriptions. An example is represented by the image of the Congo river because it appears smaller and more isolated than how it really is. This assertion is particularly important because it is the clear proof that Conrad tried to modify the real landscape in order to create an image of the country which may help him to emphasize specific details of it such as the isolated atmosphere which permeate the entire journey. [17] Moreover, as explained by Anne McClintock, there is something hidden in Congo as it appears in Heart of Darkness. She talked about an ideological shadow because she advanced the theory that the entire journey of penetration of the central Africa is like a journey into the interiority of the cosmos which is characterized by a great mystery. The voice who has to describe the landscape belongs to Marlow, but he has a crisis when it comes to elaborate a discourse about the landscape in front of his eyes. From the point of view of the scholar, Marlow cannot describe the characteristics of Congo because he experienced the classic feelings of a colonial intruder. [18]

Indeed, when he said “Going up that river was like travelling back to the earliest beginnings of the world, when vegetation rioted on the earth and the big trees were kings. An empty stream, a great silence, an impenetrable forest” [19], the image that he is trying to give to the public is that one of a primeval planet that he cannot describe because he cannot comprehend where he is. In other words, this is a great example of a colonized territory which can be identified as heterotopic place but, at the same time, as suggested by McClintock, it is the representation of this dark place that allow Conrad to denounce the atrocities and the devastation of Colonialism. [20]

Equally important, in order to understand the relevance of specific landscapes and places in these two novels, it is the notion of voice intended as propaganda and vehicle to guide the life of other people. Considering this view, it is possible to identify The Day of Creation as a novel which turn around the idea of propaganda and the power of media and television. When Mallory argued that “Sanger existed in a fictionalized world, remade by the clichés of his own ‘wild-life’ nature films. These were not soap operas but soap documentaries.

The makers of TV documentaries were the conmen and carpetbaggers of the late twentieth century

the snake-oil and fast-change salesmen purveying the notion that a raw nature packaged and homogenized by science was palatable and reassuring” [21], he is trying to report and denounce how television and, specifically, the documentary on natural landscape tend to subvert reality. Indeed, Enzo Fileno Carabba said that Ballard tries to add another element to the primordial four once and it is represented by the world of media because it has the power to reshape a new political order based on the control of the human mind. [22] The tapes used by Noon, the absurd story about Mallory and the river created by Sanger with the help of his colleagues Mr. Pal and Miss Matsuoka and the constant obsession for the documentary are elements that Ballard decided to insert in order to allow the public to reflect on the intensive power of media and also to the manipulation of the truth. Furthermore, the utterance of Sanger, “Television doesn’t tell lies, it makes up a new truth. In fact, the only truth we have left These sentimental wild-life films you despise simply continue that domestication of nature which began when we cut down the first tree.They help people to remake nature into a form that reflects their real needs” [23], appears as a great anticipation of what is going to happen at the end of the novel when the entire landscapes appear as unreal and idealised place through the eyes of Sanger and Mallory.In fact, when Sanger exclaimed

“Prepare yourself, Mallory… now we reach our climax, returning to that primitive fount from which all the rivers of the earth have sprung, the moment when consciousness moved into the daylight, from the reptile to the mammalian brain… now God exists, Mallory, perhaps you have returned to Eden to destroy Him… a messiah for the age of cable television” [24],

it is clear that the real landscapes entirely disappear because the voice is able to transform the reality. In this context, Sanger, the blind man who dedicated his life to television, contributes to the manipulation of reality that Mallory creates. The colonized country is not only a heterotopic place, but it also becomes a paradise regained to the eyes of Mallory and Sanger.

The consequence of propaganda and the power of the words

are present also in Heart of Darkness. There is the voice of Marlow which is present for almost the entire story and it helps to describe the events but, at the same time, there is the allusion to another voice which is that one of Kurtz. The admiration for Kurtz’s voice is clear and it subjugates, not only the natives and the other members of the Company, but also Marlow. He said that

The man presented himself as a voice. Not of course that I did not connect him with some sort of action. Hadn’t I been told in all the tones of jealousy and admiration that he had collected, bartered, swindled, or stolen more ivory than all the other agents together. That was not the point. The point was in his being a gifted creature and that of all his gifts the one that stood out pre-eminently, that carried with it a sense of real presence, was his ability to talk, his words – the gift of expression, the bewildering, the illuminating, the most exalted and the most contemptible, the pulsating stream of light, or the deceitful flow from the heart of an impenetrable darkness. [25]

Thus, it seems that the only person who can speak in the isolated darkness of that landscape is Kurtz but, at the end, only a few words remain of his voice: “The horror! The horror!” [26]. All things considered, it is impossible to know the very meaning of these words but it is inevitable to think about the fact that Kurtz is not only the representation of the Company and a man of power, but he was also a witness of the consequences of colonialism and he saw with his eyes the effects of the exploitation of Congo. The reader will never hear Kurtz and his descriptions of the landscape of Congo but, with that words in mind, he can only try to imagine the real effects of the Western civilization on the colonized territory.

In the final analysis, it is possible to say that the way landscapes, spaces and places are used in the novels have the great power to influence the public. Thomas S. David, in fact, asserted that novelists “[…] sketch out something like a geoaesthetic, or a way of imagining the planet itself as intimately and inseparably related to human histories” [27]. Indeed, the aesthetic of certain fictional creations is strictly connected to the idea of combining the real world with paradoxical universe because writers such as J. G. Ballard urge to reflect on the relationship between the human species and its own existence on the planet.[28] In this context, Science Fiction writers pay great attention to the realization of specific landscapes which do not belong to this world. In other words, these places are the product of imagination and it is through the journey of the human experience in these unreal worlds that people can reflect on their existence in the modern society.

In essence, Science Fiction writers reflects on the modern reality because they urge to comprehend the impact and the possible effects of progress. It is possible to say that, on the one hand, they analyse the modern world in order to discover what human mind cannot see and, on the other hand, they try to investigate on the past centuries to better comprehend the evolution of the world. With this in mind, colonialism has a great impact on Science Fiction because it is one of the fundamental process that Science Fiction writers decide to focus on. All things considered, the idea advanced by Rieder who said that “The antithetical relation of colonial or imperial triumphalism to science fictional catastrophes is in some instances a straightforward matter of the fiction’s reversing the positions of colonizer and colonized, master and slave, core and periphery” [29] is a clear example of how Science Fiction writers decide to approach to colonialism. In the modern society, the colonized territory is represented by the spaces of people’s daily life because everyone can be a victim of the progress. In other words, Science Fiction writers reinterpret the concept of colonialism and they show how human mind can be colonized by the effect of the progress. The Day of Creation, in this context, is an example of how landscapes, ideologies and people can be transformed by the impact of the Western civilization.

- [13] Enzo Fileno Carabba, “Il pre-socratico post-atomico”, in Il Futuro è morto. Psicogeografia della modernità, ed. Tiziana Villani (Milano: Mimesis, 1995), 125 – 127.

- [14] J. G. Ballard, The Day of Creation, (London: Fourth Estate, 2014), 97.

- [15] W. Warren Wagar, “J. G. Ballard and the Transvaluaion of Utopia”, Science Fiction Studies, 18, no. 1 (Mar. 1991): 53.

- [16] W. Warren Wagar, “J. G. Ballard and the Transvaluation of Utopia”, 55.

- [17] Mark D. Larabee, The Historian’s Heart of Darkness. Reading Conrad’s Masterpiece as Social and Cultural History, (Santa Barbara, California: Praeger. 2018), 35 – 37.

- [18] Anne McClintock, “Unspeakable Secrets”: The Ideology of Landscape in Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness”, The Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association 17, no. 1 (Spring 1984), 39 – 43.

- [19] Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness, (New York – London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2017), 33.

- [20] McClintock, “Unspeakable Secrets”: The Ideology of Landscape in Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness”, 52.

- [21] Ballard, The Day of Creation, 42 – 43.

- [22] Fileno Carabba, “Il pre-socratico post-atomico”, 125.

- [23] Ballard, The Day of Creation, 47;

- [24] Ballard, The Day of Creation, 230;

- [25] Conrad, Heart of Darkness, 47;

- [26] Conrad, Heart of Darkness, 69;

- [27] Thomas S. Davis, “Fossils of Tomorrow: Len Lye, J. G. Ballard and the Planetary Futures”, MFS Modern Fiction Studies 64, no. 4 (Winter 2018);

- [28] Thomas S. Davis, “Fossils of Tomorrow: Len Lye, J. G. Ballard and the Planetary Futures”, 673 – 675;

- [29] Rieder, Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction, 124;

Bibliography

Primary Sources

- Ballard, J. G. (2014) The Day of Creation. London: Fourth State;

- Conrad, J. (2017) Heart of Darkness. New York – London: W. W. Norton & Company;

Secondary Sources

- J. Ballard (1992), “The Visitor.” Interview by Phil Halper and Lard Iyer, Hardcore Magazine, https://www.jgballard.ca/media/1992_hardcore_magazine.html;

- Csicsery-Ronay, Jr., Istvan, “Science Fiction and Empire.” Science Fiction Studies 30, no 2, Social Science Fiction (Jul. 2003): 231 – 245;

- Davis, Thomas S. “Fossils of Tomorrow: Len Lye, J. G. Ballard, and the Planetary Futures.” MFS Modern Fiction Studies 64, no. 4 (Winter 2018): 659-679;

- Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias.” In Rethinking Architecture: A Reader in Cultural Theory, edited by N. Leach, 329 – 336. NYC: Routledge, 1997.

- Larabee, Mark D. (2018)The Historian’s Heart of Darkness. Reading Conrad’s Masterpiece as Social and Cultural History. Santa Barbara, California: Praeger.

- McClincock, Anne. “‘Unspeakable Secrets’: The Ideology of Landscape in Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’.” The Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association 17, no. 1 (Spring 1984): 38 – 53.

- Rieder, J. (2008) Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

- Stableford, B. (2006). Science Fact and Science Fiction: An Encyclopaedia. New York: Routledge.

- Stockwell, P. (2000). The Poetics of Science Fiction. New York: Routledge.

- Villani, T, (1995), ed. Il futuro è morto. Psicogeografia della modernità. Milano: Mimesis.

- Warren, Wagar, W. “J- G. Ballard and the Transvaluation of Utopia.” Science Fiction Studies 18, no. 1 (Mar. 1991): 53 – 70.

Articolo di

Sonia Aiello