H.G. Wells’ theory of human non-evolution

“And they revert. As soon as my hand is taken from them the beast begins to creep back, begins to assert itself again.” –Dr. Moreau

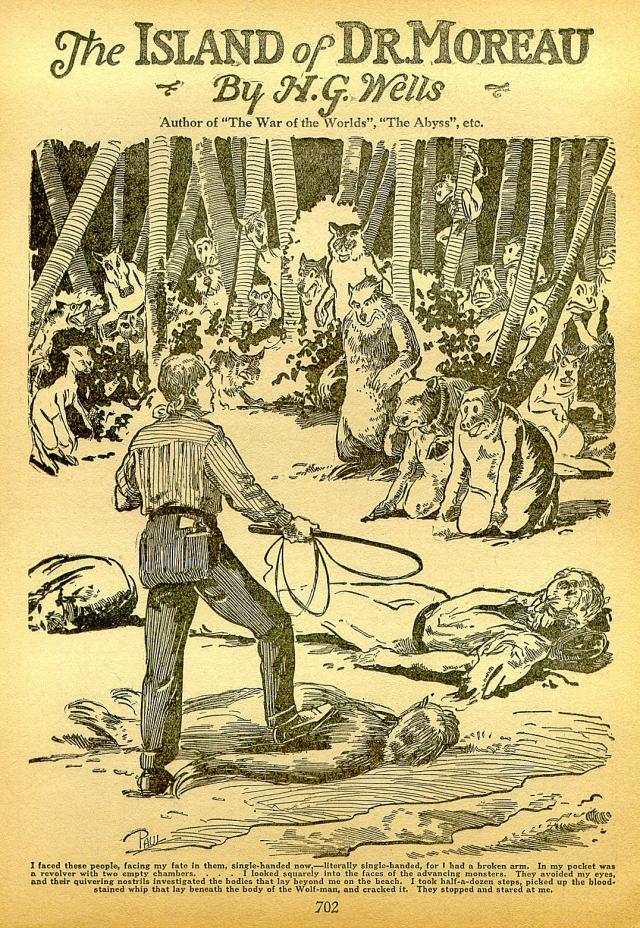

H.G. Wells, the father of science fiction, was born in England in 1866 and lived through the Victorian Age as a Socialist. He is widely known for works such as The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897) and The War of the Worlds (1898). In this paper I will analyse Wells’ vision of human evolution. Or rather, human non-evolution. Wells strongly believed that mankind hasn’t changed since Paleolithic and that men would likely revert to that state if society and education suddenly disappeared from the face of Earth. The author wrote a lot about this topic in his early essays, but it all can be summed up in his second novel The Island of Doctor Moreau.

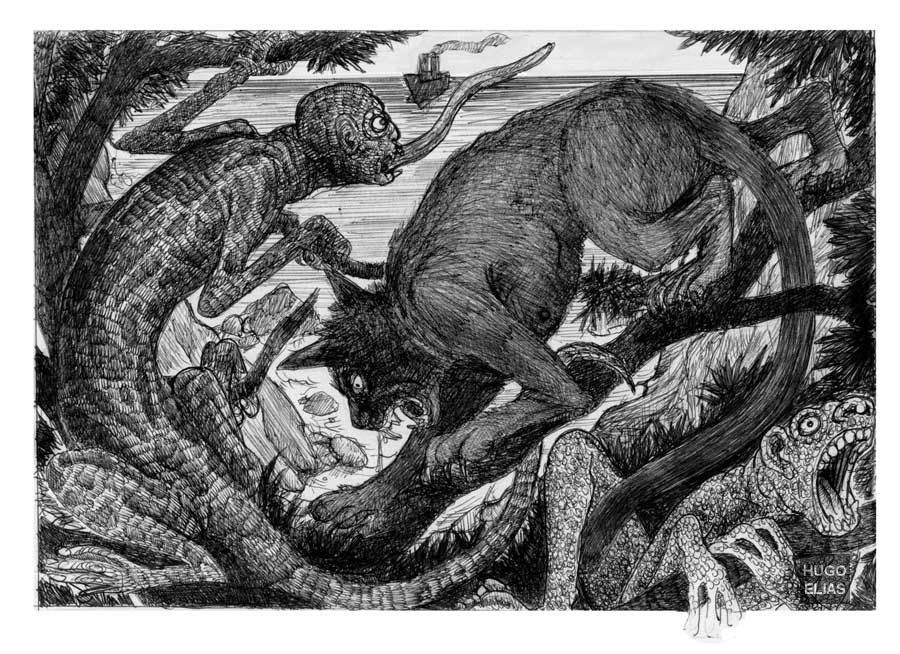

The story is about a young Englishman named Prendick who survives a shipwreck and is saved by a passing ship. Aboard this ship are the drunk Captain, a man named Montgomery, his servant M’ling and a cargo of animals. The ship is approaching a mysterious island which is where Montgomery is headed with his cargo. As the crew reaches the destination, the drunken captain forces Prendick to leave and Montgomery takes the survivor with him out of pity. The island belongs to a man called Dr. Moreau, who was known in London as a physiologist who made cruel experiments on animals and was forced to leave the country because of that. The island is inhabited by some weird creatures that resemble men but have something strange about them, as they look more like animals. Eventually Prendick enters one of the rooms where the Doctor works only to find a humanoid covered in bandages. He then believes that the Doctor made experiments on human beings and flees into the jungle where he meets more of these creatures who he calls Beast Folk. As they see Prendick, they invite him to join a ritual, a chanting in glory of Moreau, in which they mention a Law.

‘It is a man. He must learn the Law. […] Say the words. Not to go on all-fours; that is the Law,’ it repeated in a kind of sing-song. I was puzzled. ‘Say the words,’ said the Ape-man, repeating, and the figures in the doorway echoed this, with a threat in the tone of their voices. I realised that I had to repeat this idiotic formula; and then began the insanest ceremony. The voice in the dark began intoning a mad litany, line by line, and I and the rest to repeat it. As they did so, they swayed from side to side in the oddest way, and beat their hands upon their knees; and I followed their example. I could have imagined I was already dead and in another world. That dark hut, these grotesque dim figures, just flecked here and there by a glimmer of light, and all of them swaying in unison and chanting, ‘Not to go on all-fours; that is the Law. Are we not Men? ‘Not to suck up Drink; that is the Law. Are we not Men? ‘Not to eat Fish or Flesh; that is the Law. Are we not Men? ‘Not to claw the Bark of Trees; that is the Law. Are we not Men? ‘Not to chase other Men; that is the Law. Are we not Men?[1]

This Law is chanted by a grey creature called The Sayer of the Law.

‘I am the Sayer of the Law,’ said the grey figure. ‘Here come all that be new to learn the Law. I sit in the darkness and say the Law.’ ‘It is even so,’ said one of the beasts in the doorway. ‘Evil are the punishments of those who break the Law. None escape.’ ‘None escape,’ said the Beast Folk, glancing furtively one another.[2]

The following day, Prendick sees Moreau looking for him with a revolver in his hand, and flees. In the end he gets cornered and threatens Moreau that he would drown himself rather than becoming one of his creatures. Moreau then laughs it off, hands the revolver to Prendick and leads him back to his shelter, where he will explain everything. He did vivisection experiments on animals in order to turn them into men, not the opposite. The following passage is vital as it explains Wells’ and Moreau’s vision of the role of education. Moreau claims that he dedicated his life to “the plasticity of living forms”[3].

It is a possible thing to transplant tissue from one part of an animal to another, or from one animal to another; to alter its chemical reactions and methods of growth: to modify the articulations of its limbs; and, indeed, to change it in its most intimate structure. […] ‘But,’ said I, ‘ these things—these animals talk!’ He said that was so, and proceeded to point out that the possibility of vivisection does not stop at a mere physical metamorphosis. A pig may be educated. The mental structure is even less determinate than the bodily. In our growing science of hypnotism we find the promise of a possibility of supersending old inherent instincts by new suggestions, grafting upon or replacing the inherited fixed ideas. Very much indeed of what we call moral education, he said, is such an artificial modification and perversion of instinct; pugnacity is trained into courageous self-sacrifice, and suppressed sexuality into religious emotion.

As stated in this paper before, education is what makes a man Man. Moreau desperately vivisected animals in order to allow them to talk so to educate them and finally recreate Mankind. As Prendick accuses the Doctor of torturing animals and giving them pain, he replies that pain is irrelevant in front of the importance of science. It is not but a little thing.

The capacity for pain is not needed in the muscle, and it is not placed there – is but little needed in the skin, and only here and there over the thigh is a spot capable of feeling pain. Pain is simply our intrinsic medical adviser to warn us and stimulate us. Not all living flesh is painful; nor is all nerve, not even all sensory nerve. […] Then with men, the more intelligent they become, the more intelligently they will see after their own welfare, and the less they will need the goad to keep them out of danger. I never yet heard of a useless thing that was not ground out of existence by evolution sooner or later. Did you? And pain gets needless. […] This store which men and women set on pleasure and pain, Prendick, is the mark of the beast upon them – the mark of the beast from which they came![4]

Pain and pleasure are something that only beasts/uneducated people might consider. As a matter of fact, Wells/Moreau considers them an obstacle towards true evolution. Men live in order to avoid pain and seek pleasure. But if men are willing to sacrifice these two primordial elements, true evolution will be finally at hand, not only in terms of becoming more intelligent. We know now that this is not necessarily true, as Wells could’ve never known about DNA, and through DNA we found out that evolution are just mutations that our genetic code underwent.[5] According to Wells, education is essential to not revert back to the primitives. In fact, we didn’t grow any extra limb, tooth, fang or any other mechanism of self-defence.

Yes, we managed to change other things, like digesting milk, but still, if a man today grew up in the woods, he would grow beast-like. That is because in DNA are kept genetic information and harmless mutations, but not education, or history, or morality. Hypothetically, if a man lived in the woods today for their whole life with no other human contact, they could never know that they could digest milk now, but couldn’t in the past. That’s the role of education. To be aware of constantly evolving, to keep track of changes. Wells spent a lot of energy over this as the Victorian scientific community was tied to sociology as well. Even though Wells did not know about DNA, he had a brilliant intuition: he figured that in evolution, nothing is fixed. The main goal of The Island of Doctor Moreau is to make this clear to the society he lived in. Victorian society firmly believed that humans were the top of the evolutionary tree, a superior species, and Wells wanted people to think twice before making that assertion. [6] The Doctor’s attempts to recreate human through vivisection look promising at first, but then the animals simply revert to their original state and instinct.

‘Then I took a gorilla I had; and upon that, working with infinite care and mastering difficulty after difficulty, I made my first man. All the week, night and day, I moulded him. With him it was chiefly the brain that needed moulding: much had to be added, much changed. I thought him a fair specimen of the negroid type when I had finished him […]

I spent many days educating the brute – altogether I had him for three or four months. I taught him the rudiments of English; gave him ideas of counting; even made the thing read the alphabet. But at that he was slow, though I’ve met with idiots slower. He began with a clean sheet, mentally; had no memories left in his mind of what he had been. When his scars were quite healed, and he was no longer anything but painful and stiff, and able to converse a little, I took him yonder and introduced him to the Kanakas as an interesting stowaway.

[…] I rested from work for some days after this, and was in a mind to wrote an account of the whole affair to wake up English physiology. Then I came upon the creature squatting up in a tree and gibbering at two of the Kanakas who had been teasing him. I threatened him, told him the inhumanity of such a proceeding, aroused his sense of shame, and came home resolved to do better before I took my work back to England. I have been doing better. But somehow the things drift back again: the stubborn beast-flesh grows day by day back again. But I mean to do better things still. I mean to conquer that.[7]

The Beast Folk following the Law is pure hypnosis. Moreau considers this Law a mockery human life.

In spite of their increased intelligence and the tendency of their animal instincts to reawaken, they had certain fixed ideas implanted by Moreau in their minds, which absolutely bounded their imaginations. They were really hypnotised; had been told that certain things were impossible, and that certain things were not to be done, and these prohibitions were woven into the texture of their minds beyond any possibility of disobedience or dispute.

It definitely sounds like the things we call education and morality. Aren’t we all told what is wrong and what is right? What is it possible and what is not? Education and morality lower our primordial instincts so to allow us to live in society. If we remove them, we revert, just like the Beast Folk do, as we don’t have any restrictions. More about this line of thought can be read in the following passage:

There is an idea abroad that the average man is improving by virtue of the same impetus that raised him above the apes, an idea that finds its expression in such works, for instance, as Mr. Kidd’s ‘Social Evolution’. If I read that very suggestive author right, he believes that “Natural Selection” is “steadily evolving” the intrinsic moral qualities of man. It is, however, possible that Natural Selection is not the agent at work here. For Natural Selection is selection by Death. It may help to clarify an important question, to point out what is certainly not very clearly understood at present, that the evolutionary process now operating in the social body is one essentially different from that which has differentiated species in the past and raised man to his ascendency among the animals. Assuming the truth of the Theory of Natural Selection, having regard to Professor Weismann’s destructive criticism of the evidence for the inheritance of acquired characters, there are satisfactory grounds for believing that man (allowing for racial blendings) is still mentally, morally, and physically, what he was during the later Paleolithic period, that we are, and that the race is likely to remain, for (humanly speaking) a vast period of time, at the level of the Stone Age. The only considerable evolution that has occurred since then, so far as man is concerned, has been, it is here asserted, a different sort of evolution altogether, an evolution of suggestions and ideas.

[…]

If the child of civilised man, by some conjuring with time, could be transferred, at the moment of its birth, to the arms of some Paleolithic mother, it is conceivable that it would grow up a savage in no way superior, by any standards, to the true-born Paleolithic savage. The main difference is extrinsic, it is a difference in the scope and nature of the circle of thought, and it arose, one may conceive, as a result of the development of speech. Slowly during the vast age of unpolished stone, this new and wonderful instrument of intellectual enlargement and moral suggestion, replaced inarticulate sounds and gestures. Out of speech, by no process of natural selection, but as a necessary consequence, arose tradition. With true articulate speech came the possibilities of more complex co-operations and instructions than had hitherto been possible, more complex industries than hunting and chipping of flints, and, at last, after a few thousand years, came writing, and therewith a tremendous acceleration in the expansion of that body of knowledge and ideals which is the reality of the civilised state.[8]

(Second part of this thesis will be published on 15th of July)

Note:

- [1] H. G. Wells, The Island of Doctor Moreau, 1896, pp.71-72

- [2] Ibid., pp.74

- [3] Ibid., pp.88

- [4] Ibid., pp.92

- [5] I. Murnaghan, Evolution of DNA, 2016, available at http://www.exploredna.co.uk/evolution-dna.html

- [6] John McNabb, The Beast Within: H.G. Wells, The Island of Doctor Moreau, and human evolution in the mid-1890s, pp.3-4

- [7] H. G. Wells, The Island of Doctor Moreau, pp. 94-95

- [8] H. G. Wells, Human Evolution, an Artificial Process. In R. M. Philmus, D. Y. Hughes, H. G. Wells: Early Writings in Science and Science Fiction, University of California Press, pp.211-216.

Articolo di

Fabrizio Orlando

2 commenti su “To educate or to revert – first part”